ARGENTINA'S ECONOMIC ,CORRUPTION PROBLEMS AND THE FAILED WAR ON DRUGS.ARGENTINA CONTINUES TO BE MIRED IN CLIMATE OF CORRUPTION AND ECONOMIC REPRESSION IN THE PUBLIC SECTORS.

The President of Argentina hosted the official launch of the Argentine G20

presidency: the world’s major forum for economic, political, and financial

cooperation.This will be the first G20 presidency in South America and for Argentina

an opportunity to help craft global policy.

The President of Argentina hosted the official launch of the Argentine G20

presidency: the world’s major forum for economic, political, and financial

cooperation.This will be the first G20 presidency in South America and for Argentina

an opportunity to help craft global policy.

In

the 2015 presidential election and Argentines said it was time for a

change. Cambiemos! With less than a year under his belt, President Macri

settled the multi-billion dollar debt with its holdout creditors, sold

global bonds to the tune of

$16.5 billion (an emerging market record), eliminated foreign exchange

restrictions, established a floating exchange rate , suspended the

export tax on all agriculture (except soya), passed a tax amnesty bill

for its citizens and cut government spending in areas such as gas, water

and electricity. Despite the fact that these swift global moves have

created some domestic turmoil, including an increase in inflation and

unemployment rates, Argentina’s profile is getting more “Likes” these

days. Macri also kicked alliances with Venezuela and friends to the curb

in favor of a free trade deal with the United States. International

companies have taken notice and major players like GM, Dow Chemical and

American Energy Partners are taking a chance on Argentina. Coca-Cola and

Fiat-Chrysler are also getting roses: the former has pledged to invest

$1 billion over the next four years and the latter is spending $500

million to upgrade its automotive plant in Cordoba.,

the country elected President Mauricio Macri.The country’s first

democratically elected leader in the last hundred years to not be either

a populist or a militarist. During his term, he has instituted many

free-market policies that have

benefited investors, but these policies have also had harmful effects

on small businesses. Argentina’s economy has been shrinking in the last

year, and unemployment is almost at 10 percent. Macri’s approval rating

has gone down 18 percentage points to 54 percent, and Argentine citizens

are now protesting in the streets. In order to accurately explain this

political instability, one needs to understand the short-term economic

losses and long-term economic gains behind his policies.Macri took

office with a lot on his plate. The tumultuous history of Argentina

includes dictatorships and failed socialist regimes. The country was in

default from 2001 to 2016 and reached 21 percent unemployment in 2002.

Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, the previous president, instituted

protectionist policies that squashed foreign competition and implemented

currency controls that overvalued the peso. In addition, Argentina has

been experiencing high inflation for over a decade and has underinvested

in infrastructure. Krichner’s administration was filled with multiple

corruption scandals, including fraud, and was notorious for manipulating

statistics. Although a regional power in the 1980s, Argentina's last

decade has been one of isolation and economic loss.Once in office, Macri

implemented policies, ranging from infrastructural upgrades to major

improvements in the quality of government statistics, to stimulate the

economy and cater to businesses. Importantly, Macri also cut the export

tax, ended currency controls, and lowered subsidies. Despite how

sensible many of these reforms sound, the average Argentine has not yet

seen the benefits—in fact, for many, things have gotten much worse. The

economy shrank 4.3 percent from June 2015 to June 2016, unemployment hit

9.3 percent in the second quarter, and in July, industrial production

had a 7.9 percent loss.

Argentina’s

former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchnerrefused to testify in a

fraud probe.The Kirchners were Peronistas, meaning that they swore

allegiance to the enduring

political phenomenon inspired by Juan Domingo Perón, the late President

whose legacy is so confoundingly multifarious that it has acquired

adherents on the left and right, like some kind of multihued national

cloak. The Kirchners adopted a leftist course, siding with the late Hugo

Chávez and the Castros in world affairs, while lambasting the United

States. Kirchner engaged in a long-running feud with the media

conglomerate Grupo Clarín, accusing it of having a Mafia-like hold over

the flow of information in Argentina. Later, she took on international

debt speculators, calling them “vultures” and refusing to pay them, in

what became a prolonged and, for Argentina’s credit rating, deleterious

standoff.

Argentina’s

former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchnerrefused to testify in a

fraud probe.The Kirchners were Peronistas, meaning that they swore

allegiance to the enduring

political phenomenon inspired by Juan Domingo Perón, the late President

whose legacy is so confoundingly multifarious that it has acquired

adherents on the left and right, like some kind of multihued national

cloak. The Kirchners adopted a leftist course, siding with the late Hugo

Chávez and the Castros in world affairs, while lambasting the United

States. Kirchner engaged in a long-running feud with the media

conglomerate Grupo Clarín, accusing it of having a Mafia-like hold over

the flow of information in Argentina. Later, she took on international

debt speculators, calling them “vultures” and refusing to pay them, in

what became a prolonged and, for Argentina’s credit rating, deleterious

standoff.

Like

all Latin American countries, Argentina has a tumultuous history, one

tainted by periods of despotic rule, corruption and hard times. But it’s

also an illustrious history, a story of a country that was once one of

the world’s economic powerhouses, a

country that gave birth to the tango, to international icons like Evita

Perón and Che Guevara, and to some of the world’s most important

inventions Understanding Argentina’s past is paramount to understanding

its present and, most importantly, to understanding Argentines

themselves.rruption

in Argentina remains a serious problem. Argentina has long suffered

from widespread and endemic corruption. Corruption remains a serious

problem in the public and private sector even though the legal and

institutional framework combating corruption is strong in Argentina.

While corruption exists in all levels of society, businesses should

note the especially high risk in public procurement. Argentina's

anti-corruption

provisions are largely contained in the Criminal Code , which prohibits

the active and passive bribery of public officials and bribery of

foreign public officials. The Code does not provide an exception for

facilitation payments, and gifts are prohibited, but enforcement of

anti-corruption provisions is lacking. Companies consider irregular

payments and bribes to be a standard way of conducting business in many

sectors.Corruption, especially in the form of political manipulation, is

a high risk in the judiciary. Companies report that exchanges of

irregular payments and bribes to obtain favorable judicial decisions

often occur . With the exception of the Supreme Court, the judicial

system can be subject to political interference, especially in

provincial courts . In early 2015, Argentinians took to the streets in a

huge march to demonstrate their discontent with the lack of judicial

independence Companies demonstrate a

low confidence in the efficiency of Argentina's judiciary in settling

disputes and in challenging regulations.Despite the availability of

local investment dispute adjudication through local courts or

administrative procedures, many investors prefer private or

international arbitration, likely due to judicial inefficiency Enforcing

a contract is less costly and less time-consuming than Latin American

averages Argentina has ratified the

United Nations' Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign

Arbitral Awards and is a member state to the International Center for

the Settlement of Investment Disputes.Argentina's police carries a high

risk of corruption. The police force is among the most corrupt

institutions in the country and its actions are cited as arbitrary and

politicized . Businesses report that the police cannot be consistently

relied upon to enforce law and order .In an

attempt to curb corruption, in 2014 the metropolitan police of Buenos

Aires adopted a model of community policing that grants higher pay and

benefits to its officers . The Oficina Anticorrupción , Argentina's

anti-corruption agency, has an internal mechanism through which civil

servants can complain about police actions.Transparency

International's 2016 Corruption Perception Index ranks the country 95th

place out of 176 countries The Financial Action Task Force removed

Argentina from its "gray list" in October 2014, noting significant

progress made by the country in improving its legislation and procedures

against money laundering and illicit financing.The

former president of Argentina was indicted on charges of leading a

money laundering scheme while in office, yet another legal blow to the

ex-leader who is facing mounting corruption charges and

allegations.Former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

(2007-2015) was officially indicted on April 4 by Argentine judge

Claudio Bonadio for allegedly leading a money laundering ring, reported

Clarín.Charges were also formally brought against the ex-president’s two

children, Maximo and Florencia, as well as businessmen Cristóbal López

and Lázaro Báez, the latter of whom is currently incarcerated and

awaiting trial for a separate public funds embezzlement case.Fernández

has not been formally charged with any wrongdoing, but federal

prosecutor Guillermo Marijuán on Saturday “imputed” her. In Argentina’s

legal system, that means the prosecutor feels there is enough evidence

to warrant a full-scale investigation that could result in charges.The

prosecutor moved against the still-popular former president after

hearing 12 hours of testimony by Leonardo Fariña, an imprisoned former

associate of businessman and alleged Fernández frontman Lázaro Báez.In a

plea bargain, Fariña implicated Fernández and her late husband and

former president Nestor Kirchner in a case related to money laundering

and embezzling funds earmarked for public works. Baez was

arrested.According to press reports, Fariña testified to the movement

out of Argentina by Fariña and Báez of tens and possibly hundreds of

millions of dollars, money that was transferred through offshore

companies in Panama, Belize and the Seyschelles to a Swiss bank.The

leftist leader, from the Peronist party, was barred constitutionally

from seeking a third consecutive term.

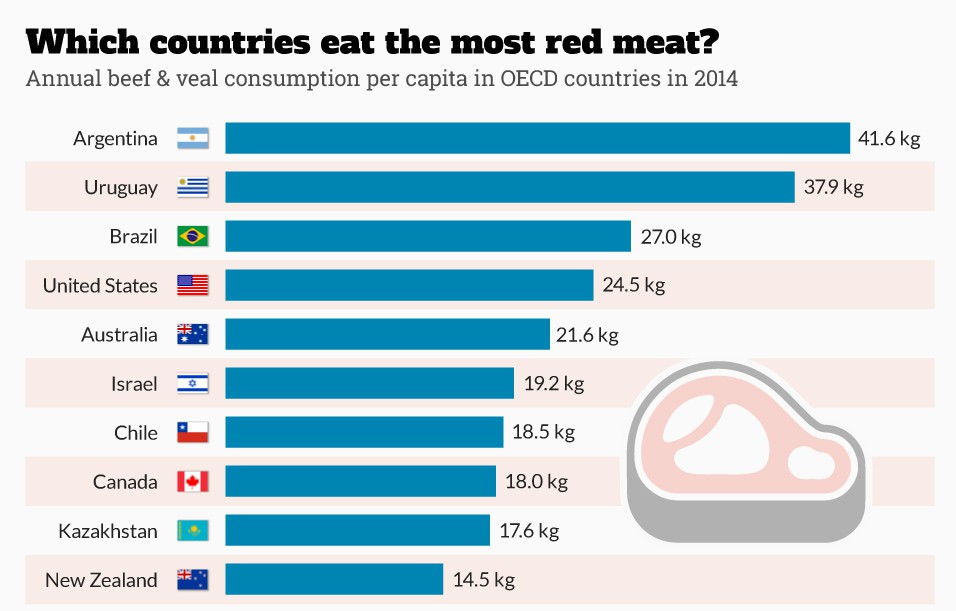

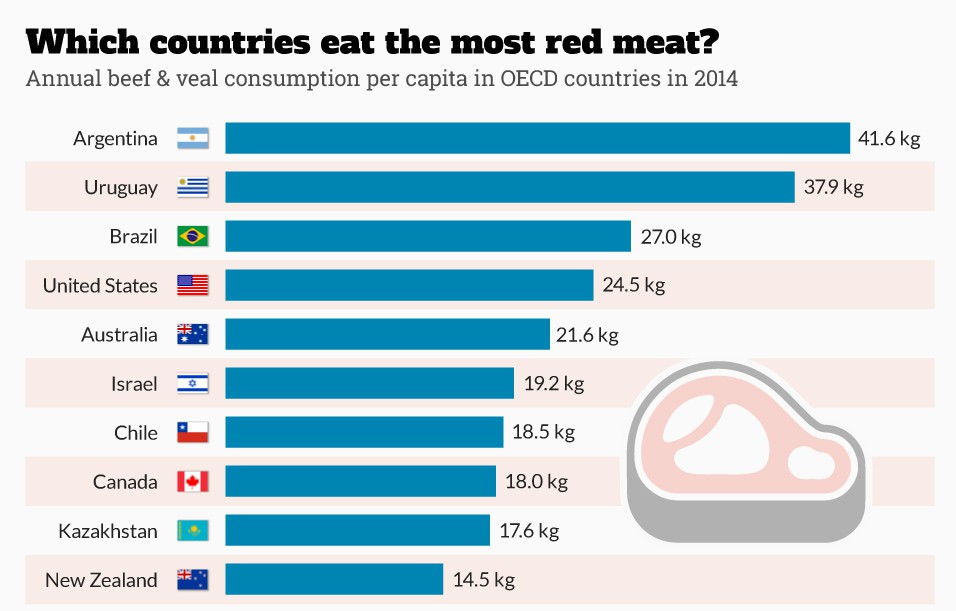

Argentina

is the world’s largest consumer of red meat, with beef featuring in

many dishes. “Parillas’’ are restaurants that specialise in barbecued

meat. Typical dishes and foods include asado (BBQ meat), empanadas

(pasties), picadas (cold meats and cheeses

accompanied by bread), mate (herbal tea), dulce de leche (caramelised

condensed milk) and alfajores (sweet biscuits filled with dulce de

leche). The low leverage of the Argentinian private sector (28% of GDP),

expected monetary easing as inflation edges lower, a doubling of USD

deposits in the bank system in 2016 and access to cheap international

finance after 15 years of isolation should help these

investment expectations materialize. All in all, we expect economic

activity to grow by 2.5% y-o-y in 2017 and by 3.7% y-o-y in 2018, driven

by a pick- up in private consumption and investments . Actually, we see

Argentina becoming one of the fastest growing economy in South America

in the coming two years.

Argentina

is the world’s largest consumer of red meat, with beef featuring in

many dishes. “Parillas’’ are restaurants that specialise in barbecued

meat. Typical dishes and foods include asado (BBQ meat), empanadas

(pasties), picadas (cold meats and cheeses

accompanied by bread), mate (herbal tea), dulce de leche (caramelised

condensed milk) and alfajores (sweet biscuits filled with dulce de

leche). The low leverage of the Argentinian private sector (28% of GDP),

expected monetary easing as inflation edges lower, a doubling of USD

deposits in the bank system in 2016 and access to cheap international

finance after 15 years of isolation should help these

investment expectations materialize. All in all, we expect economic

activity to grow by 2.5% y-o-y in 2017 and by 3.7% y-o-y in 2018, driven

by a pick- up in private consumption and investments . Actually, we see

Argentina becoming one of the fastest growing economy in South America

in the coming two years.

Economic

growth is projected to strengthen and become more broad-based.

Inflation is falling, as monetary policy remains restrictive, raising

households’ purchasing power and lifting consumer spending.

Infrastructure outlays, improvements in the business environment and

rising capital flows will boost investment. Exports will benefit from

the recovery in Brazil. The labour market will improve gradually as the

recovery picks up.Fiscal

policy will be moderately contractionary to reduce the deficit while

safeguarding the recovery. Monetary policy will remain appropriately

restrictive to bring down double-digit inflation. Growth and jobs would

be boosted by wide-ranging structural reforms, including a comprehensive

tax reform to simplify the system and improve fairness. Efforts to

reduce inequalities in access to quality education would make growth

more inclusive.The

financial system remains small. Bank credit to the private sector and

stock market capitalisation are well below the levels of OECD countries.

Long-term finance is almost non-existent, constraining investment and

growth. Household and corporate sector debt are low. The main challenge

for financial stability will be to monitor and avoid vulnerabilities as

the financial sector expands.In 2001, the economic crisis gave rise to bitter political

disputes among Argentina’s ruling class. A major row over economy

ministers took place in March, and a "lack of national unity" in

Congress almost provoked de la Rúa to resign in

the summer. In the fall, Cavallo sought to grab money from the

provinces to apply toward the external debt. During the last week of

October, he urged de la Rúa to break the national agreement that has

guaranteed the provinces a minimum of 1.3 billion pesos in tax sharing

transfers. Yet the provincial governors, who remain under intense

pressure from protesters to resist federal austerity measures, walked

out of negotiations after Cavallo declared they should accept payment in

federal IOUs instead of cash.Angry over the

deepening crisis and the weakness of the government’s response,

Argentine voters delivered a damning blow to de la Rúa and his governing

Alianza coalition on October 14. Results gave the Peronist Partido

Justicialista (PJ) control of both the Congress and the Senate in an

unusual campaign in which Alianza incumbents often found themselves

running against members of their own parties, the center-left Radical

Party and the smaller Frepaso. Despite a mandatory voting law, voter

turnout was the lowest since the end of the military dictatorship in

1983.In Buenos Aires, the number of deliberately

spoiled ballots surpassed the number of votes for any one candidate.

Several polling stations noticed a number of votes cast for the cartoon

character "Clemente." And 50 ballot envelopes contained an unknown white

powder.On

December 19, 2001, food riots erupted in se veral Argentine cities.

Within hours, the riots escalated into a broad protest against th e

government and social unrest unfolded into a full institutional debacle.

Two administrations collapsed in less than

two weeks, the country defaulted on the service of its debt, and

political instability returned to the country after eighteen y ears of

democratic rule. This essay traces the development of the Argentine

political crisis and argues that this episode illustrates a rising trend

in Latin America. The first part of this paper explores the unfolding

of the crisis and its resolution. The second part compares the Argentine

case with seven other similar episodes that took place in Latin America

after 1990. I conclude that a new model of political instability

characterized by low military intervention, high popular mob ilization,

and a critical role of congress—is emerging in the region.With

its debt issues mostly resolved and exchange controls eliminated,

Argentina is open for business. Like any recent divorcee just getting

back in the dating game, there’s going to be a learning curve. Times

have changed and Argentina is considered afrontier

market. International investors see potential in frontier markets

because as less established, pre-emerging markets, the risk may be high,

but so is the potential return. Not that adventurous, but still want to

be a Global Citizen? It might be wise to balance riskier investments in

frontier or developing economies with an investment that gives you

broad-based global exposure to developed economies, as well as the

potential growth in regions like South America and Asia-Pac.Argentina

has long been a transit point for drug shipments from Andean countries

and across its shared border with Paraguay and Brazil. Its manufacturing

labs and local drug markets have expanded in recent years, according to

the country’s attorney general.

Subsequently, increases in marijuana and cocaine seizures in 2015. Not

surprisingly, the 2015 World Drug Report ranked Argentina as the most

frequently mentioned cocaine transit country over a 10-year period. Two

years before, the same report had placed Argentina third in the ranking,

behind Colombia and Brazil.In another case, three major ephedrine

suppliers with ties to Mexican cartels were murdered execution-style in

Buenos Aires.

Macri,

the leading opposition candidate, has named the fight against drug

trafficking as one of three main challenges his administration would

focus on. Earlier this year, he said: “It’s putting our culture, our

families at risk. It is also corrupting our

institutions; buying politicians, judges, police officers and

officials, and it must be stopped. We will be the first government to

address this issue directly and battle it from the first day.” One of

the battles Macri is specific about winning the one against the

by-product of cocaine, paco. During the presidential debate on 4th

October, Macri promised to eradicate the drug within five years.Argentina

has long been a transit point for drug shipments from Andean countries

and across its shared border with Paraguay and Brazil. Its manufacturing

labs and local drug markets have expanded in recent years, according to

the country’s attorney general.

Subsequently, the U.S. Department of State and the United Nations

Office on Drug and Crime also reported increases in marijuana and

cocaine seizures in 2015. Not surprisingly, the 2015 World Drug Report

ranked Argentina as the most frequently mentioned cocaine transit

country over a 10-year period. Two years before, the same report had

placed Argentina third in the ranking, behind Colombia and Brazil.In

another case, three major ephedrine suppliers with ties to Mexican

cartels were murdered execution-style in Buenos Aires. Public outrage

ensued, and Cristina Kirchner launched a highly publicized crackdown on

the internal drug trade, Insight Crime reported. Although the crackdown

on the distribution of chemical precursors to narcotics had only a mild

effect, the late response came under fire, especially since

pharmaceutical companies represented some of Kirchner’s top campaign

donors.Between national defense and homeland security.The last time that

the government reformed federal agencies, in the 1990s, it left

security forces and the criminal justice system untouched.The Federal

Police, Gendarmerie, and Coast Guard operate under institutional and

organizational models nearly a half-century old.On this front, Macri has

agreed that the treatment of addicts should be prioritized through

early-intervention and consumption reduction programs, with a special

emphasis on paco He would also reform the state-run SEDRONAR, which

works to reduce the supply and demand of drugs and oversees prevention

policies.Regarding the creation of an agency against organized crime,

Gorgal said that the most important task for criminal intelligence was

the consolidation of information from judges and federal agencies.

Using resources for this purpose would be more cost-effective, since

there are already four security agencies in charge of prosecuting

drug-trafficking organizations.He emphasized how more criminal

intelligence could be a first step to understand regional patterns of

drug smuggling and money laundering. “Argentina is operating in the

shadows,” . Macri will have to develop accountability systems, such as

impact evaluations for prosecutors and police chiefs, so corrupt public

servants answer for their choices on the job.Yet to seriously dissipate

public safety concerns, Macri will not only have to implement reforms

that address these broader symptoms of insecurity, but also restore the

lost confidence in institutions.

Human

migration to the Americas began nearly 30, 000 years ago, when the

ancestors of Amerindians, taking advantage of lowered sea levels during

the Pleistocene epoch, walked from Siberia to Alaska via a land bridge

across the Bering Strait. Not exactly speedy about moving south, they

reached what’s now Argentina around 10, 000 BC. One of Argentina’s

oldest and impressive archaeological sites is Cueva de las Manos in

Patagonia, where mysterious cave paintings, mostly of left hands, date

from 7370 BC.By the time the Spanish arrived, much of present-day

Argentina was inhabited by highly mobile peoples who hunted the guanaco

(a wild relative of the llama) and the rhea (a large bird resembling an

emu) with bow and arrow or boleadoras – heavily weighted thongs that

could be thrown up to 90m to ensnare the hunted animal.The Argentine

pampas was inhabited by the Querandí, hunters and gatherers who are

legendary for their spirited resistance to the Spanish. The Guaraní,

indigenous to the area from northern Entre Ríos through Corrientes and

into Paraguay and Brazil, were semisedentary agriculturalists, raising

sweet potatoes, maize, manioc and beans, and fishing the Río Paraná.Of

all of Argentina, the northwest was the most developed. Several

indigenous groups, most notably the Diaguita, practiced irrigated

agriculture in the valleys of the eastern Andean foothills. The region’s

inhabitants were influenced heavily by the Tiahanaco empire of Bolivia

and by the great Inca empire, which expanded south from Peru into

Argentina from the early 1480s. In Salta province the ruined stone city

of Quilmes is one of the best-preserved pre-Incan indigenous sites,

where some 5000 Quilmes, part of the Diaguita civilization, lived and

withstood the Inca invasion. Further north in Tilcara you can see a

completely restored pucará , about which little is known.In the Lake

District and Patagonia, the Pehuenches and Puelches were

hunter-gatherers, and the pine nuts of the araucaria, or pehuén tree,

formed a staple of their diet. The names Pehuenches and Puelches were

given to them by the Mapuche, who entered the region from the west as

the Spanish pushed south. Today there are many Mapuche reservations,

especially in the area around Junín de los Andes, where you can still

sample foods made from pine nuts.Vice-royalty of La Plata: 1776-1810.For

the first two centuries of the Spanish empire the vast region draining

from the Andes to the river Plate at Buenos Aires is the least regarded

part of Latin America. It lacks the gold or silver which attract

adventurers across the Atlantic to Mexico and Peru. There is no direct

link with Spain, all official contact being through the viceregal

capital at Lima. Most of the early settlements are established by

colonists moving into the region from Peru or Chile. In 1726 Buenos

Aires has a population of only 2200.But the area's status gradually

improves during the 18th century, particularly after an administrative

reorganization in 1776.Until this time the region has been part of the

viceroyalty of Peru, administered at very long range from Lima. In 1776

the entire area, from the eastern Bolivian highlands through Paraguay,

Uruguay and Argentina to the southern tip of the continent, is given

separate status as the viceroyalty of La Plata with its capital at

Buenos Aires.The people of Buenos Aires discover an exciting new sense

of pride in 1806, after a British fleet arrives and captures the city.

The Spanish viceroy flees ignominiously, whereupon Creole militia led by

Santiago de Liniers expel the intruders on their own. For three years

Liniers rules in place of the absent viceroy. Buenos Aires is now in the

mood to seize any future opportunities.Argentina and San Martín:

1810-1816.Argentina takes its first step towards independence more

easily than most other regions of the Spanish empire, partly because of

the events of 1806-9 in Buenos Aires. When developments in Spain in 1808

force a choice of allegiance, a cabildo abierto (open town meeting) in

Buenos Aires on 25 May 1810 quickly decides to set up an autonomous

local government on behalf of the deposed Ferdinand VII.However this

first step is soon followed by violent conflict with opposing royalist

forces elsewhere in the province. News of this conflict brings back to

Buenos Aires an Argentinian-born officer serving in the Spanish army,

José de San Martín.When San Martín reaches Argentina in 1812, the

patriot army is under the command of Manuel Belgrano, a Buenos Aires

lawyer who has had his first military experience as a member of the

Creole militia in 1806. In the early years of the war of independence

Belgrano has successes against royalist troops in the foothills of the

Andes in the extreme northwest of Argentina, at Tucuman (1812) and Salta

(1813). But he is defeated further north, in Bolivia, later in 1813. In

1814 he is replaced as commander by San Martín.These battles have all

been close to the main source of royalist strength, the rich and

conservative viceroyalty of Peru. San Martin concludes that Latin

America's independence will never be secure until Peru is conquered.The

independence of Argentina is formally proclaimed on 9 July 1816,

abandoning any pretence that the junta has been governing on behalf of

Ferdinand VII. (The decision is simplified by the reactionary and

incompetent rule of the Spanish king after he recovers his throne in

1814.) Meanwhile San Martín is assembling and training an army for his

long-term plan of campaign against Peru. He has decided on a two-pronged

attack, beginning with an invasion of Chile.He already has an important

Chilean ally in Bernardo O'Higgins, a soldier closely involved in the

beginnings of the independence movement in Chile but from 1814 a refugee

in Argentina.United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata: 1816-1828.San

Martín marches west into Chile in January 1817, a few month's after the

formal declaration of full Argentinian independence. He leaves his

compatriots in Argentina with the task of forming a nation out of what

has been the vast but relatively uncentralized viceroyalty of La

Plata.The ambitions of many in Buenos Aires are that their city should

remain the capital of the entire viceroyalty. But in 1817 this already

looks a forlorn hope. Paraguay has resolutely gone its own way in 1811

and by 1814 is a region almost impenetrable to outsiders. Uruguay

becomes a battle ground between Argentina and Brazil.

The President of Argentina hosted the official launch of the Argentine G20

presidency: the world’s major forum for economic, political, and financial

cooperation.This will be the first G20 presidency in South America and for Argentina

an opportunity to help craft global policy.

The President of Argentina hosted the official launch of the Argentine G20

presidency: the world’s major forum for economic, political, and financial

cooperation.This will be the first G20 presidency in South America and for Argentina

an opportunity to help craft global policy.  Argentina’s

former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchnerrefused to testify in a

fraud probe.The Kirchners were Peronistas, meaning that they swore

allegiance to the enduring

political phenomenon inspired by Juan Domingo Perón, the late President

whose legacy is so confoundingly multifarious that it has acquired

adherents on the left and right, like some kind of multihued national

cloak. The Kirchners adopted a leftist course, siding with the late Hugo

Chávez and the Castros in world affairs, while lambasting the United

States. Kirchner engaged in a long-running feud with the media

conglomerate Grupo Clarín, accusing it of having a Mafia-like hold over

the flow of information in Argentina. Later, she took on international

debt speculators, calling them “vultures” and refusing to pay them, in

what became a prolonged and, for Argentina’s credit rating, deleterious

standoff.

Argentina’s

former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchnerrefused to testify in a

fraud probe.The Kirchners were Peronistas, meaning that they swore

allegiance to the enduring

political phenomenon inspired by Juan Domingo Perón, the late President

whose legacy is so confoundingly multifarious that it has acquired

adherents on the left and right, like some kind of multihued national

cloak. The Kirchners adopted a leftist course, siding with the late Hugo

Chávez and the Castros in world affairs, while lambasting the United

States. Kirchner engaged in a long-running feud with the media

conglomerate Grupo Clarín, accusing it of having a Mafia-like hold over

the flow of information in Argentina. Later, she took on international

debt speculators, calling them “vultures” and refusing to pay them, in

what became a prolonged and, for Argentina’s credit rating, deleterious

standoff. Argentina

is the world’s largest consumer of red meat, with beef featuring in

many dishes. “Parillas’’ are restaurants that specialise in barbecued

meat. Typical dishes and foods include asado (BBQ meat), empanadas

(pasties), picadas (cold meats and cheeses

accompanied by bread), mate (herbal tea), dulce de leche (caramelised

condensed milk) and alfajores (sweet biscuits filled with dulce de

leche). The low leverage of the Argentinian private sector (28% of GDP),

expected monetary easing as inflation edges lower, a doubling of USD

deposits in the bank system in 2016 and access to cheap international

finance after 15 years of isolation should help these

investment expectations materialize. All in all, we expect economic

activity to grow by 2.5% y-o-y in 2017 and by 3.7% y-o-y in 2018, driven

by a pick- up in private consumption and investments . Actually, we see

Argentina becoming one of the fastest growing economy in South America

in the coming two years.

Argentina

is the world’s largest consumer of red meat, with beef featuring in

many dishes. “Parillas’’ are restaurants that specialise in barbecued

meat. Typical dishes and foods include asado (BBQ meat), empanadas

(pasties), picadas (cold meats and cheeses

accompanied by bread), mate (herbal tea), dulce de leche (caramelised

condensed milk) and alfajores (sweet biscuits filled with dulce de

leche). The low leverage of the Argentinian private sector (28% of GDP),

expected monetary easing as inflation edges lower, a doubling of USD

deposits in the bank system in 2016 and access to cheap international

finance after 15 years of isolation should help these

investment expectations materialize. All in all, we expect economic

activity to grow by 2.5% y-o-y in 2017 and by 3.7% y-o-y in 2018, driven

by a pick- up in private consumption and investments . Actually, we see

Argentina becoming one of the fastest growing economy in South America

in the coming two years.