THE YUGOSLAV CIVIL WARS (1991–1999/2001) ,EUROPE'S WORST ATROCITY SINCE THE WORLD WAR II.A MODERN GENOCIDE,THE FRAGMENTATION OF YUGOSLAVIA: NATIONALISM IN MULTINATIONAL STATE.FORMER COMMANDER BOSNIAN SERB RATKO MLADIC JAILED FOR LIFE.

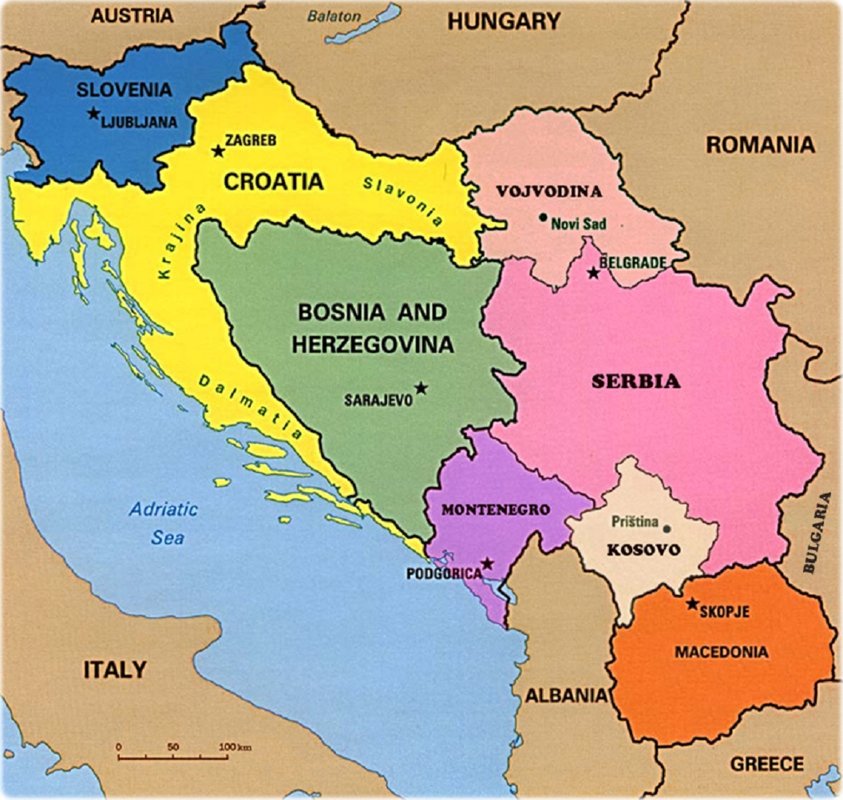

Over the first half of the 1990s, the nation-state of Yugoslavia (formally, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) experienced the secession of three its component republics: Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia. The latter two of these were bitterly fought over, both by regular troops and against civilians suddenly resistant to living in ethnically mixed settings. In 1991 and 1992, as Croatia’s military fought Yugoslavia’s, Croat and Serb civilians in both realms undertook campaigns of “ethnic cleansing” efforts by one group to rid certain areas of the other. As they did echoes resounded of World War Two-era conflicts in which the Croatian.

Over the first half of the 1990s, the nation-state of Yugoslavia (formally, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) experienced the secession of three its component republics: Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia. The latter two of these were bitterly fought over, both by regular troops and against civilians suddenly resistant to living in ethnically mixed settings. In 1991 and 1992, as Croatia’s military fought Yugoslavia’s, Croat and Serb civilians in both realms undertook campaigns of “ethnic cleansing” efforts by one group to rid certain areas of the other. As they did echoes resounded of World War Two-era conflicts in which the Croatian.

History.

Except for the Albanians, whose ancestors are believed to have been native to the region the longest, most of the inhabitants of the Western Balkans descended from Slavic tribes who migrated there from the east in around the 6th century A.D.During the first millennium the Balkans came under two major influences: the Roman Empire and the Constantinople-based Byzantine Empire, with the river Drina as the dividing line between the two. One of the Slavic tribes, the Croats, lived in Latin-controlled territories and consequently converted to Roman Catholicism, while another, the Serbs, lived in Byzantine domains and converted to Orthodox Christianity.The Byzantine Empire was gradually subsumed by the Ottoman Turks, who established an empire that had extended into the Balkans by the 1300s. The Turks introduced Islam to the region. A pivotal moment in Balkan history occurred on June 28, 1389, when the Serbs, who had been expanding their own empire since the 1200s, were defeated by the Turks at the Battle of Kosovo, ushering in five centuries of Turkish domination.Meanwhile, the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty was expanding into Croat and Slovene lands. The Hungarians also were a strong presence, often vying with the Austrians for supremacy, especially in Croatia.Ottoman and Hapsburg rule involved multiple and often-shifting alliances, creating a patchwork of ethnic groups. For example, shortly after 1578, the Austrians persuaded Serb refugees fleeing the Turks to move to Krajina in Croatia to act as a buffer against Ottoman expansion. The Austrians also persuaded some Germans and Hungarians to move to Serbian lands.Under Ottoman rule, many Bosnians converted to Islam, since they were allowed to keep their lands if they converted. Montenegro, with support from Russia, managed to resist Ottoman domination and was ruled by its own prince-bishops.Both the Hapsburgs and Ottomans fell into decline in the 1800s, having failed to keep up with modernizing trends. The conquered Slavs began to reassert their identity. By 1830 the Serbs, backed by Russia, which sought more power in the region, had succeeded in establishing an autonomous principality. The Ottoman supremacy was further weakened in 1878, when Serbs and Montenegrins successfully revolted, winning full independence. In the ensuing territorial carve-up by Europe's leading powers, Austria-Hungary was allowed to occupy Bosnia and later annexed it in 1908.Meanwhile, a Slavic cultural renaissance was taking root, with Serb and Croat scholars, for instance, agreeing in 1850 on a dialect that would form the basis of a common language, called Serbo-Croat.In the early 1900s, both the Albanian and the Slavic Balkan nations made a final push to purge their homelands of Turkish influence, causing millions of Muslims, including many Bosniaks, to flee eastward to modern-day Turkey. Albanians, who had converted to Islam during Ottoman rule, began asserting their independence as well. This created conflict with their Orthodox Christian neighbors, the Serbs, who occupied Kosovo in 1912, massacring some 20,000 Albanians.A watershed moment in Balkan and indeed world history occurred on June 28, 1914, when a Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand, who was visiting the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo. Because of the intricate web of military alliances European powers had woven during the preceding decades, the assassination plunged the continent and eventually the whole world — into World War I (1914–18).When Europe's borders were redrawn after World War I, a new country made up predominantly of south Slavic peoples was cobbled together from the ruins of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires. Initially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, it was rechristened Yugoslavia in 1929.13 A Serbian dynasty, the Karadjordjevics, became the ruling monarchy, creating tension among non-Serbs.During World War II (1939–45) Yugoslavia began to fall apart after the Axis powers, Germany and Italy, invaded in April 1941. Croats were allowed to form their own state called the Independent State of Croatia, which was essentially a Nazi puppet regime run by the fascist Ustase Party, led by nationalist politician Ante Pavelic. Initially, many Croats welcomed their independence but grew discontented after Italy began seizing large swathes of territory. The Ustase government collapsed in 1945, and its supporters, who had massacred many Serbs while in power, suffered massive reprisals.The great experiment in this Slavic nation was based on a noble idea.

Its proponents thought that south Slavs, that is to say people with

much in common, especially their languages, who lived in a great arc of

territory from the borders of Austria almost to the gates of

Constantinople (now Istanbul), should unite and form one great strong

south Slav state.Ideas for a union of the southern Slavs had begun circulating at

least as early as the 1840s. In the regions that were to become part of

modern Croatia, thinkers dreamed of a new Illyria - a name harking back

to the days of the Roman Empire. Amongst Serbs, however, such notions

were less prevalent. Serbian nationalist thinkers dreamed of recreating,

first a Serbian state and then perhaps a Serbian empire.Dreams of a union, state or empire came easily to the lands of the

south Slavs because all of the people who lived in what was to become

Yugoslavia were then the subjects of others. And the fault-lines of

empire divided the south Slavs from one another.By 1912, however, the first of the wars that were to convulse this

region periodically throughout the 20th century was about to begin. Two

small Serbian and Montenegrin states had already emerged and become

independent - having shaken off the Ottoman Turkish yoke - but the rest

of what was to become Yugoslavia was still part of either the Ottoman or

the Austro-Hungarian Empire.Within months the old order was gone.The assassination in Sarajevo

sparked off World War One, which in its wake destroyed the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. What was to replace it? Many Croat, Serb and

other south Slav soldiers remained loyal to Austria-Hungary during the

war, but there were also some who did not.Indeed, some of its politicians feared that as Austria-Hungary

crumbled Italy would seize as much of the coast of Dalmatia as it could,

while Serbia would create a new greatly enlarged Serbian state,

including Bosnia and parts of what are now Croatia - especially those

areas that were then heavily inhabited by Serbs. The politicians felt

that a deal must be reached with Serbia. A new union was to be

proclaimed. The Serbian Army would save Croatia and Slovenia from the

territorial ambitions of the Italians, and union would also save Croatia

from Serbia itself. The kingdom was formed on 1 December 1918. Serbia's

royal family, the Karadjordjevics, became that of the new country,

which was officially called the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and

Slovenes until 1929 - when it became Yugoslavia.

Josip Broz Tito,was president of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1953 to 1980.Under Tito, Yugoslavia's government lived in a paranoia of its own

making - constantly fearing invasion from NATO to the West and from the

Warsaw Pact to the East. This paranoia deepened in the days after the

leader's death. But regardless of what Tito and his cronies told the

public, their main source of fear were the citizens of Yugoslavia

themselves. It was against their potential reaction that the army was

mobilised.Autocratic regimes often dissolve suddenly and bloodily but Tito's

regime outlived him by 10 years - so strong was the grip under which he

controlled Yugoslavia. After all, staying in power was the ultimate goal

of this controversial figure.

Josip Broz Tito,was president of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1953 to 1980.Under Tito, Yugoslavia's government lived in a paranoia of its own

making - constantly fearing invasion from NATO to the West and from the

Warsaw Pact to the East. This paranoia deepened in the days after the

leader's death. But regardless of what Tito and his cronies told the

public, their main source of fear were the citizens of Yugoslavia

themselves. It was against their potential reaction that the army was

mobilised.Autocratic regimes often dissolve suddenly and bloodily but Tito's

regime outlived him by 10 years - so strong was the grip under which he

controlled Yugoslavia. After all, staying in power was the ultimate goal

of this controversial figure.

In April 1992, the government of the Yugoslav republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia. Over the next several years, Bosnian Serb forces, with the backing of the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army, targeted both Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) and Croatian civilians for atrocious crimes resulting in the deaths of some 100,000 people (80 percent Bosniak) by 1995. It was the worst act of genocide since the Nazi regime’s destruction of some 6 million European Jews during World War II.The Yugoslav Wars were a series of ethnic conflicts, wars of independence and insurgencies fought from 1991 in the former Yugoslavia which led to the breakup of the Yugoslav state, with its constituent republics declaring independence despite tensions between ethnic minorities in the new countries (chiefly Serbs, Croats and Muslims) being unresolved. The wars are generally considered to be a series of separate, but related, military conflicts which occurred in most of the former Yugoslav republics.Most wars ended through peace accords, involving full international recognition of new states, but with massive economic damage to the region. Initially the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) sought to preserve the unity of the whole of Yugoslavia by crushing the secessionist governments but it increasingly came under the influence of the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević that evoked Serbian nationalist rhetoric and was willing to use the Yugoslav cause to preserve the unity of Serbs in one state. As a result, the JNA began to lose Slovenes, Croats, Kosovar Albanians, Bosniaks, and ethnic Macedonians, and effectively became a Serb army. According to the 1994 United Nations report, the Serb side did not aim to restore Yugoslavia, but to create a "Greater Serbia" from parts of Croatia and Bosnia. Other irredentist movements have also been brought into connection with the wars, such as "Greater Albania" and "Greater Croatia".Often described as Europe's deadliest conflicts since World War II, the wars were marked by many war crimes, including ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity and rape. The Bosnian genocide was the first European crime since World War II to be formally judged as genocidal in character and many key individual participants were subsequently charged with war crimes. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established by the UN to prosecute these crimes.According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, the Yugoslav Wars resulted in the death of 140,000 people. The Humanitarian Law Center estimates that in the conflicts in the former Yugoslav republics at least 130,000 people were killed.Clear ethnic conflict between the Yugoslav peoples only became prominent in the 20th century, beginning with tensions over the constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in the early 1920s and escalating into violence between Serbs and Croats in the late 1920s after the assassination of Croatian politician.The nation of Yugoslavia was created in the aftermath of World War I, and it was mostly composed of South Slavic Christians, but the nation also had a substantial Muslim minority. This nation lasted from 1918 to 1941, when it was invaded by the Axis powers during World War II, (founded in 1929), which conducted a genocidal campaign against Serbs, Jews and Roma inside its territory and the Chetniks, who also conducted their own campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide towards ethnic Croats and Bosniaks, while also supporting the reinstating of the Serbian royals. In 1945, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) was established under Josip Broz Tito, who maintained a strongly authoritarian leadership that suppressed nationalism. After Tito's death in the 1980s, relations among the six republics of the SFRY deteriorated. Slovenia and Croatia desired greater autonomy within the Yugoslav confederation, while Serbia sought to strengthen federal authority. As it became clearer that there was no solution agreeable to all parties, Slovenia and Croatia moved toward secession. Although tensions in Yugoslavia had been mounting since the early 1980s, it was 1990 that proved decisive. In the midst of economic hardship, Yugoslavia was facing rising nationalism among its various ethnic groups. By the early 1990s, there was no effective authority at the federal level. The Federal Presidency consisted of the representatives of the six republics, two provinces, and the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). The communist leadership was divided along national lines.The representatives of Vojvodina, Kosovo and Montenegro were replaced with loyalists of the President of Serbia Slobodan Milošević .Serbia secured four out of eight federal presidency votes and was able to heavily influence decision-making at the federal level, since all the other Yugoslav republics only had one vote. While Slovenia and Croatia wanted to allow a multi-party system, Serbia, led by Slobodan Milošević, demanded an even more centralized federation and Serbia's dominant role in it. At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in January 1990, the Serbian-dominated assembly agreed to abolish the single-party system; however, Slobodan Milo?evi?, the head of the Serbian Party branch (League of Communists of Serbia) used his influence to block and vote-down all other proposals from the Croatian and Slovene party delegates. This prompted the Croatian and Slovene delegations to walk out and thus the break-up of the party, a symbolic event representing the end of "brotherhood and unity".Upon Croatia and Slovenia declaring independence in 1991, the Yugoslav federal government attempted to forcibly halt the impending breakup of the country, with Yugoslav Prime Minister Ante Markovi? declaring the secessions of Slovenia and Croatia to be illegal and contrary to the constitution of Yugoslavia, and declared support for the Yugoslav People's Army to secure the integral unity of Yugoslavia.War in the Balkans 1941-1945, the ethnically mixed region of Dalmatia held close and amicable relations between the Croats and Serbs who lived there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many early proponents of a united Yugoslavia came from this region, such as Ante Trumbi?, a Croat from Dalmatia. However, by the time of the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars, any hospitable relations between Croats and Serbs in Dalmatia had broken down, with Dalmatian Serbs fighting on the side of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.Even though the policies throughout the entire socialist period of Yugoslavia seemed to have been the same , Dejan Guzina argues that "different contexts in each of the subperiods of socialist Serbia and Yugoslavia yielded entirely different results . He assumes that the Serbian policy changed from conservative-socialist at the beginning to xenophobic nationalist in the late 1980s and 1990s.

The Yugoslav war,ultimately,

it was Nationalist Serbia that ignited Yugoslavia, the embrace of

decades-old nationalism that endorsed expansionism and revenge would be

the basis for the wars and the ‘horrors’ that followed. We can clearly

see a progression of Nationalist Serb aggression from Milosevic’s rise

to power in the mid-1980s- The oppressive measures taken against Kosovo

in 1987, the ‘Bureaucratic revolution’ and the gradual trampling of the

Yugoslav constitution, the embrace and encouragement of Serbian

nationalism- one that openly promoted violence, racism and xenophobia

towards non-Serbs and finally, control and use of the JNA and various

Nationalist-Serb military forces used to attack Slovenia, Croatia,

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, respectively.

The Yugoslav war,ultimately,

it was Nationalist Serbia that ignited Yugoslavia, the embrace of

decades-old nationalism that endorsed expansionism and revenge would be

the basis for the wars and the ‘horrors’ that followed. We can clearly

see a progression of Nationalist Serb aggression from Milosevic’s rise

to power in the mid-1980s- The oppressive measures taken against Kosovo

in 1987, the ‘Bureaucratic revolution’ and the gradual trampling of the

Yugoslav constitution, the embrace and encouragement of Serbian

nationalism- one that openly promoted violence, racism and xenophobia

towards non-Serbs and finally, control and use of the JNA and various

Nationalist-Serb military forces used to attack Slovenia, Croatia,

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, respectively.

Croatian War of Independence (1991-1995)

To understand Croatia’s war in the 1990s, one needs to understand the historical background, as well as geopolitical interests of the international community, neighbours and international powers and all of those interests before, during and after the war, as well as in the future.Croatia was, and still is, the hottest piece of geographic real estate in Europe. Croatia is the gateway between north, south, east and west in Europe. Therefore, it is no surprise that two of the worlds’ largest empires expanded onto Croatian territory, namely the Austro-Hungarian (Hapsburg) Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Smaller powers also coveted Croatian territory, for instance, Serbia and Venice and later the Italian state.It must be noted that Croatia joined in union with Hungary first, in 1102, with its arrangement changing with Hungary’s union with Austria.Croatia’s position within the Hapsburg Empire, which it joined in 1527 (later Austria Hungary), was one of continual de jure statehood and self-rule within empire and with Hungary, albeit with varying degrees of de facto statehood and self-rule shifting within the context of the Austrian-Hungarian power struggles, coupled with external pressure (the Ottomans).Croatia was continually trying to not only reclaim historical territory, but also gain equal legal and political footing with both Austria and Hungary, joining either one or the other in internal political struggles; with either Austria or Hungary aligning with political actors within Croatia, to and include the Serb minority, whom the Austrians began settling in Croatia without Croatian consent beginning in 1533, who over the centuries were used as a political hammer against Croats by both the Austrians and Hungarians.Croatia’s history is a long and complicated one.However the war in the 1990s is traced directly to Croatia’s entry into both Yugoslavias.The first Yugoslavia was the end objective outlined by the state of Serbia which entailed the domination of Croatia and Croats by Serbia, outlined in 1833 by Serbian Minister of the Interior Ilja Garasanin.Croats in the first Yugoslavia were second class citizens in an occupied country. Serbian state sponsored violence and terrorism enforced nationalist Serbian policies, which were economically exploitive of Croatia.This state terrorism culminated with the assassination of the pacifist Croatian politician Stjepan Radic, Croatian Peasant Party head, in Parliament while in session in 1928. The CPP had the overwhelming support of Croats inside and outside of Croatia proper before, during and after Radic’s death, through to WWII.The Serbian “King” Aleksandar Karadjordjevic (who married United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland Queen Victoria’s great-granddaughter Princess Maria of Romania) declared a royal dictatorship in 1929 – a day later the Ustasha movement (UHRO) formed under Ante Pavelic, the Croatian Party of Rights leader who personally witnessed the state murder of Radic. The repression became worse, leading to over 30,000 political arrests of mostly Croats, and, the emigration of tens of thousands of Croats over the next decade.However the Croatian question was still festering. Despite Albert Einstein and Heinrich Mann’s denunciation of state-sponsored terrorism in Yugoslavia, the repression of Croats, and their open call for Croatian independence, no Western democracy called for any pressure against Belgrade for their imperialism.In the end, the Allies won WWII and the Communist Partisans took over Croatia and all the territory that was the first Yugoslav Kingdom. The Communist “liberation” saw hundreds of thousands of Croatians killed without trial, death marches, the imprisonment and internment of over 1.2 million Yugoslav citizens (the bulk of them Croatian), and one-party rule under the dictator Josip Broz Tito whom the Yugoslav state controlled media and Communist intelligentsia created a bizarre cult of personality worship for. In the second Yugoslavia, Croatia saw a continuation of the same cultural imperialism of the first Yugoslavia, and the concept of “Yugoslav” was the same as before, it was supra-nationalist code for Serbian. The 1954 Novi Sad Language Agreement standardized the use of Serbian under the red herring of Serbo-Croatian.Yugoslavia was a failed economic model. The first reason was that the economy itself was propped up on foreign credit, thanks in part due to Tito’s rejection of Joseph Stalin, which gained him Western support as the Cold War was ongoing. The lavish credits from the West (and USSR, which also payed Tito to stay neutral) was poorly reinvested into the Yugoslav economy, which was run by unqualified Communists who were mostly given positions due to party membership, not technical knowledge of anything.The second reason was that, by the 1980s, even the Communists estimated that the work force was 40 percent “ghost,” meaning non-productive.The third reason is that basic infrastructure and long-term projects were rejected out of entirely political reasons, the Zagreb-Split highway for instance, a critical development project, was rejected for fears of Croatian economic development which could in turn mean more Croatian calls for autonomy, or more influence within Yugoslavia, if not help lead to independence, despite more tourist revenues meaning more money for the central government which was through various legal and illegal means, siphoning Croatia’s and Slovenia’s revenues disproportionately through higher tax rates and state-owned schemes.This failed economic model was compounded by the failed political model, which led to the inevitable failure of the state.The one-party system was backwards, as were its leaders. The political system Tito led mimicked that of the Austro-Hungarians before him – a carrot and stick approach playing various nations and or minorities off of each other to maintain a status quo of power.The biggest disruption came with the Croatian Spring, which was brutally repressed. As a consolidation, the 1974 Constitution was passed, and it, on paper, met some of the Croats’ demands, namely of more autonomy, and it gave Vojvodina and Kosovo (within Serbia) autonomy as well.Tito’s death in 1980 coincided with the decline of the USSR.Yugoslavia was no longer important because the USSR was fading into oblivion. Credits were not being pumped into it, but were being called. This caused a domino effect within the painted rust that was the entirely mismanaged and gravely grafted Yugoslav economy which was now faced with paying off lavish loans with an economy that could not even theoretically meet even the most generous payment plans.With Tito gone and inflation out of control, the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences (SANU) wrote, and the Serbian media published in 1986, the SANU Memorandum, which was a hysterical, victim-centred propaganda text that not only brought up nearly every single nationalist Serb myth, but also several Communist myths, demonising Croats, Slovenes and Albanians in particular, and more or less openly threatened all non-Serbs with a not-very-coded ‘surrender to our will or suffer the consequences’ message.Damage after the bombing of Dubrovnik .Destroyed Serbian house in Sunja, Croatia. Most Serbs fled during Operation Storm in 1995.Fighting in Croatia had begun weeks prior to the Ten-Day War in Slovenia. The Croatian War of Independence began when Serbs in Croatia, who were opposed to Croatian independence, announced their secession from Croatia.After the 1990 parliamentary elections in Croatia, Franjo Tuđman came to power and became the first President of Croatia. He promoted nationalist policies and had a primary goal of the establishment of an independent Croatia. The new government proposed constitutional changes, reinstated the traditional Croatian flag and coat of arms and removed the term "Socialist" from the title of the republic. In an attempt to counter changes made to the constitution, local Serb politicians organized a referendum on "Serb sovereignty and autonomy" in August 1990. Their boycott escalated into an insurrection in areas populated by ethnic Serbs, mostly around Knin, known as the Log Revolution. Local police in Knin sided with the growing Serbian insurgency, while many government employees, mostly in police where commanding positions were mainly held by Serbs and Communists, lost their jobs. The new Croatian constitution was ratified in December 1990, when the Serb National Council proclaimed the SAO Krajina.Ethnic tensions rose, fueled by propaganda in both Croatia and Serbia. On 2 May 1991, one of the first armed clashes between Serb paramilitaries and Croatian police occurred in the Battle of Borovo Selo. On 19 May an independence referendum was held, which was largely boycotted by Croatian Serbs, and the majority voted in favour of the independence of Croatia. Croatia declared independence and dissolved its association with Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. Due to the Brioni Agreement, a three-month moratorium was placed on the implementation of the decision that ended on 8 October.The armed incidents of early 1991 escalated into an all-out war over the summer, with fronts formed around the areas of the breakaway SAO Krajina. The JNA had disarmed the Territorial Units of Slovenia and Croatia prior to the declaration of independence, at the behest of Serbian President Slobodan Milo?evi?. This was aggravated further by an arms embargo, imposed by the UN on Yugoslavia. The JNA was ostensibly ideologically unitarian, but its officer corps was predominantly staffed by Serbs or Montenegrins (70 percent). As a result, the JNA opposed Croatian independence and sided with the Croatian Serb rebels. The Croatian Serb rebels were unaffected by the embargo as they had the support of and access to supplies of the JNA. By mid-July 1991, the JNA moved an estimated 70,000 troops to Croatia. The fighting rapidly escalated, eventually spanning hundreds of square kilometers from western Slavonia through Banija to Dalmatia.A JNA M-84 tank disabled by a mine laid by Croat soldiers in Vukovar in November 1991.Border regions faced direct attacks from forces within Serbia and Montenegro. In August 1991, the Battle of Vukovar began, where fierce fighting took place with around 1,800 Croat fighters blocking JNA's advance into Slavonia. By the end of October, the town was almost completely devastated from land shelling and air bombardment. The Siege of Dubrovnik started in October with the shelling of UNESCO world heritage site Dubrovnik, where the international press was criticised for focusing on the city's architectural heritage, instead of reporting the destruction of Vukovar in which many civilians were killed. On 18 November 1991 the battle of Vukovar ended after the city ran out of ammunition. Vukovar massacre occurred shortly after Vukovar's capture by the JNA. Meanwhile, control over central Croatia was seized by Croatian Serb forces in conjunction with the JNA Corps from Bosnia and Herzegovina, under the leadership of Ratko Mladić.In January 1992, the Vance Plan proclaimed UN controlled (UNPA) zones for Serbs in territory claimed by Serbian rebels as the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) and brought an end to major military operations, though sporadic artillery attacks on Croatian cities and occasional intrusions of Croatian forces into UNPA zones continued until 1995. The fighting in Croatia ended in mid-1995, after Operation Flash and Operation Storm. At the end of these operations, Croatia had reclaimed all of its territory except the UNPA Sector East portion of Slavonia, bordering Serbia. Most of the Serb population in the reclaimed areas became refugees, and these operations led to war crimes trials by the ICTY against elements of the Croatian military leadership in the Trial of Gotovina et al. Generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were found guilty of "war crimes and crimes against humanity" in the first instance verdict, but were acquitted on appeal in 2012. The areas of "Sector East", unaffected by the Croatian military operations, came under UN administration (UNTAES), and were reintegrated to Croatia in 1998 under the terms of the Erdut Agreement.

Three faces of Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, who was indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1995 for his role in the ethnic cleansing of Serb-held areas of Bosnia: (left) while still in office, 1996; (centre) after his disappearance, in disguise as Dr. Dragan David Dabić, an expert in alternative medicine; and (right) at the ICTY in 2008. Karadžić was found guilty of 10 of the 11 counts against him, including the crime of genocide against the residents of Srebrenica, and he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Three faces of Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, who was indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1995 for his role in the ethnic cleansing of Serb-held areas of Bosnia: (left) while still in office, 1996; (centre) after his disappearance, in disguise as Dr. Dragan David Dabić, an expert in alternative medicine; and (right) at the ICTY in 2008. Karadžić was found guilty of 10 of the 11 counts against him, including the crime of genocide against the residents of Srebrenica, and he was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Bosnian War (1992-1995)

People waiting in line to gather water during the Siege of Sarajevo.In 1992, conflict engulfed Bosnia and Herzegovina. The war was predominantly a territorial conflict between the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina chiefly supported by Bosniaks, the self-proclaimed Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska, and the self-proclaimed Herzeg-Bosnia, who were led and supplied by Serbia and Croatia respectively, reportedly with a goal of the partition of Bosnia.The Yugoslav armed forces had disintegrated into a largely Serb-dominated military force. Opposed to the Bosnian-majority led government's agenda for independence, and along with other armed nationalist Serb militant forces, the JNA attempted to prevent Bosnian citizens from voting in the 1992 referendum on independence. This did not succeed in persuading people not to vote and instead the intimidating atmosphere combined with a Serb boycott of the vote resulted in a resounding 99% vote in support for independence.On 19 June 1992, the war in Bosnia broke out, though the Siege of Sarajevo had already begun in April after Bosnia and Herzegovina had declared independence. The conflict, typified by the years-long Sarajevo siege and Srebrenica, was by far the bloodiest and most widely covered of the Yugoslav wars. Bosnia's Serb faction led by ultra-nationalist Radovan Karad?i? promised independence for all Serb areas of Bosnia from the majority-Bosniak government of Bosnia. To link the disjointed parts of territories populated by Serbs and areas claimed by Serbs, Karad?i? pursued an agenda of systematic ethnic cleansing primarily against Bosnians through massacre and forced removal of Bosniak populations.At the end of 1992, tensions between Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks rose and their collaboration fell apart. In January 1993, the two former allies engaged in open conflict, resulting in the Croat-Bosniak War. In 1994 the US brokered peace between Croatian forces and the Bosnian Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Washington Agreement. After the successful Flash and Storm operations, the Croatian Army and the combined Bosnian and Croat forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, conducted an operation codenamed Operation Mistral to push back Bosnian Serb military gains.Together with NATO air strikes on the Bosnian Serbs, the successes on the ground put pressure on the Serbs to come to the negotiating table. Pressure was put on all sides to stick to the cease-fire and negotiate an end to the war in Bosnia. The war ended with the signing of the Dayton Agreement on 14 December 1995, with the formation of Republika Srpska as an entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina being the resolution for Bosnian Serb demands.The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the United States reported in April 1995 that 90 percent of all the atrocities in the Yugoslav wars up to that point had been committed by Serb militants. Most of these atrocities occurred in Bosnia. In 2004, the ICTY ruled that the Srebrenica massacre constituted genocide. In May 2013, in a first-instance verdict, the ICTY convicted six Herzeg-Bosnia Officials for their participation in a joint criminal enterprise against Muslim population in Bosnia and Herzegovina. On 24 March 2016, Radovan Karad?i?, former president of Republika Srpska, was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment. On 22 November 2017, Ratko Mladi?, former Chief of Staff of the Army of the Republika Srpska, was sentenced to life in prison by ICTY for 10 charges, one of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and four of violations of the laws or customs of war.In Bosnia, Muslims represented the largest single population group by

1971. More Serbs and Croats emigrated over the next two decades, and in a

1991 census Bosnia’s population of some 4 million was 44 percent

Bosniak, 31 percent Serb, and 17 percent Croatian. Elections held in

late 1990 resulted in a coalition government split between parties

representing the three ethnicities (in rough proportion to their

populations) and led by the Bosniak Alija Izetbegovic. As tensions built

inside and outside the country, the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan

Karadzic and his Serbian Democratic Party withdrew from government and

set up their own “Serbian National Assembly.” On March 3, 1992, after a

referendum vote (which Karadzic’s party blocked in many Serb-populated

areas), President Izetbegovic proclaimed Bosnia’s independence.Far from seeking independence for Bosnia, Bosnian Serbs wanted to be

part of a dominant Serbian state in the Balkans–the “Greater Serbia”

that Serbian separatists had long envisioned. In early May 1992, two

days after the United States and the European Community recognized Bosnia’s independence, Bosnian Serb

forces with the backing of Milosevic and the Serb-dominated Yugoslav

army launched their offensive with a bombardment of Bosnia’s capital,

Sarajevo. They attacked Bosniak-dominated town in eastern Bosnia,

including Zvornik, Foca, and Visegrad, forcibly expelling Bosniak

civilians from the region in a brutal process that later was identified

as “ethnic cleansing.” Ethnic cleansing differs from genocide in that

its primary goal is the expulsion of a group of people from a

geographical area and not the actual physical destruction of that group,

even though the same methods–including murder, rape, torture and

forcible displacement may be used.Though Bosnian government forces tried to defend the territory,

sometimes with the help of the Croatian army, Bosnian Serb forces were

in control of nearly three-quarters of the country by the end of 1993,

and Karadzic’s party had set up their own Republika Srpska in the east.

Most of the Bosnian Croats had left the country, while a significant

Bosniak population remained only in smaller towns. Several peace

proposals between a Croatian-Bosniak federation and Bosnian Serbs failed

when the Serbs refused to give up any territory. The United Nations

(U.N.) refused to intervene in the conflict in Bosnia, but a campaign

spearheaded by its High Commissioner for Refugees provided humanitarian

aid to its many displaced, malnourished and injured victims.Rape in Bosnia Inspired Holocaust Survivors to Talk About Their Experiences During the Holocaust.The path to this discussion has been paved by developments only seen with the passage of time.Men made up the bulk of those who interviewed survivors in the first 40 years after the war, Goldenberg says, and they may have been reluctant to raise the question of rape. But after mass rapes during the Bosnian War of the 1990s came to light.During the Bosnian war, Serb forces conducted sexual abuse strategy on Bosniak/Bosnian girls and women which will later be known as mass rape phenomenon. Between 20,000 and 44,000 women were systematically raped by the Serb forces. Considering the estimates and the demographics of Bosnia, by the end of the war approximately up to seven out of every hundred sexually capable Bosniak women and girls had been raped by Serb forces. The women and young girls were often held captives for up to 8 months or more, before being released or killed, often strategically beyond the possibility of abortion. During this time they were kept under constant fear, trauma, threat, violence, oppression, humiliation, sexual abuse and slavery by soldiers in ages ranging from 20 to 60 years.Common profound complications among surviving women and girls include gynaecological, physical and psychological (post traumatic) disorders, as well as unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. The survivors often feel uncomfortable/frustrated/sickened with men, sex and relationships; ultimately affecting the growth/development of a population and/or society as such (thus constituting a slow genocide according to some). In accordance with the Bosnian society, most of the girls not married were virgins at the time of rape; further traumatizing the situation.Among the most appalling and deplorable accounts of inhuman treatment and cruelty brought upon young Muslim females of Bosnia is that of the 12-year-old Almira Bektovic, a helpless war victim for whom virtually no compassion was shown whatsoever. Born in the town of Mostar in the year 1980, she lived in Miljevina in the municipality of Foca, the birth village of her father, Ramiz Bektovic, at the time of the Serb attack on these areas in the summer of 1992. Her father was taken away by the Serbs in june 1992 and was never seen again. Almira and her mother were instead detained in the Partizan Sports Hall with hundreds of other Bosniak women and girls under inhuman conditions and with lack of food or water. In mid-August 1992, Almira Bektovic among other girls was brought to ‘Karaman’s house’ by Radovan Stankovic, this lasted for ten days until she was returned to her mother whom she told that “she had worked as a waitress, washed clothes, cleaned and cooked, and that there were many other girls there who did chores and things for the Serb soldiers”. One of the surviving witnesses from Karaman’s house reported that Almira was brought to the house holding her doll tightly to her chest, apparently not knowing what was awaiting her. Soon thereafter Nedo Samardzic raped Almira Bektovic and reportedly bragged about “having taken her virginity” and “having fooled soldier Pero Elez (who was always looking for virgins) in who was to be the first to take her virginity”.Almira was found crying and vomiting after the assault by one the surviving girls from the house. Over the next three months Almira Bekotvic was forced into much the same pattern as all the other women and girls detained in the house; she had to do household chores, cook for the soldiers and sexually please these, at the age of merely 12. Almira’s status however was even more vulnerable than that of the other girls who (in contrast to Almira) were ‘assigned’ to specific soldiers who got to rape them only, Almira thus not being assigned to any specific soldier was free to be raped by any soldier that was granted entrance to Karaman’s house. Radomir kovac detained, between or about 31 October 1992 until December 1992 Almira Bektovic (and other girls).During their detention they were also beaten, threatened, psychologically oppressed, and kept in constant fear. During this period Almira was moved between various locations and apartments in Foca in order to ‘serve’ Serb soldiers and friends of Radomir Kovac. At one or more occasions she was forced into sex with 50-year-old soldier Slavo Ivanovic. On about 25 December 1992, Radomir Kovac sold Almira Bektovic to a Montenegrin soldier .Dedicated to all the Bosnian women and girls who suffered in the aggression on Bosnia and still have an overwhelming grief in their hearts and minds.Slobodan Milosevic was born in 1941 in Pozarevac, the Republic of Serbia.He graduated from the Faculty of Law, University of Belgrade in 1964.He is married and has two children, a son Marko and a daughter Marija . His wife, Dr.Mirjana Markovic is a full professor at the University of Belgrade.He started his successful business career as economic adviser to the Mayor of Belgrade. Most of his professional life he worked in the economic and banking sectors. For a number of years he was at the head of the well known Yugoslav enterprise "Tehnogas" as its General Manager, after which he became President of "Beogradska Banka", the largest bank in Serbia and Yugoslavia.

Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician and the President of Serbia (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) from 1989 to 1997 and President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1997 to 2000.He appears before the U.N. war crimes tribunal in The Hague. This would have been unimaginable at the time of its creation when Milosevic, Karadzic and Mladic were parties to peace negotiations. Like a cat, the ICTY had several lives. Milošević conducted his own defence in the five-year-long trial, which ended without a verdict when he died in his prison cell in The Hague in 11 March 2006.

Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician and the President of Serbia (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) from 1989 to 1997 and President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1997 to 2000.He appears before the U.N. war crimes tribunal in The Hague. This would have been unimaginable at the time of its creation when Milosevic, Karadzic and Mladic were parties to peace negotiations. Like a cat, the ICTY had several lives. Milošević conducted his own defence in the five-year-long trial, which ended without a verdict when he died in his prison cell in The Hague in 11 March 2006.

Kosovo War (1998-1999)

The Kosovo War was a quick and highly destructive conflict that displaced 90 percent of the population. The severity of the unrest in Kosovo and the involvement of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) brought the Kosovo conflict to international attention in the late 1990’s. The conflict led to the displacement of thousands and lasting tension between Serbs and Albanians. The brutality of the war is largely credited with launching The Borgen Project, a humanitarian organization that has helped hundreds of thousands of people.A Tomahawk cruise missile launches from the aft missile deck of the USS Gonzalez on March 31, 1999.Post-strike bomb damage assessment photograph of the Kragujevac Armor and Motor Vehicle Plant Crvena Zastava, Serbia.Smoke in Novi Sad, Serbia after NATO bombardment in 1999After September 1990 when the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution had been unilaterally repealed by the Socialist Republic of Serbia, Kosovo's autonomy suffered and so the region was faced with state organized oppression: from the early 1990s, Albanian language radio and television were restricted and newspapers shut down. Kosovar Albanians were fired in large numbers from public enterprises and institutions, including banks, hospitals, the post office and schools. In June 1991 the University of Pri?tina assembly and several faculty councils were dissolved and replaced by Serbs. Kosovar Albanian teachers were prevented from entering school premises for the new school year beginning in September 1991, forcing students to study at home.Later, Kosovar Albanians started an insurgency against Belgrade when the Kosovo Liberation Army was founded in 1996. Armed clashes between the two sides broke out in early 1998. A NATO-facilitated ceasefire was signed on 15 October, but both sides broke it two months later and fighting resumed. When the killing of 45 Kosovar Albanians in the Ra?ak massacre was reported in January 1999, NATO decided that the conflict could only be settled by introducing a military peacekeeping force to forcibly restrain the two sides. After the Rambouillet Accords broke down on 23 March with Yugoslav rejection of an external peacekeeping force, NATO prepared to install the peacekeepers by force. The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia followed, an intervention against Serbian forces with a mainly bombing campaign, under the command of General Wesley Clark. Hostilities ended 2½ months later with the Kumanovo Agreement. Kosovo was placed under the governmental control of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo and the military protection of Kosovo Force (KFOR). The 15-month war had left thousands of civilians killed on both sides and over a million displaced.The Kosovo War was waged in the Serbian province of Kosovo from 1998 to 1999. Ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo faced the pressure of Serbs fighting for control of the region. Albanians also opposed the government of Yugoslavia, which was made up of modern day Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia and Macedonia.Muslim Albanians were the ethnic majority in Kosovo. The president of Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic, refused to recognize the rights of the majority because Kosovo was an area sacred to the Serbs. He planned to replace Albanian language and culture with Serbian institutions.The international community failed to address the escalation of tension between the Albanians and the Serbs. In doing so, they inadvertently supported radicals in the region. Ethnic Albanians in Kosovo formed the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in the early 1990s. The militant group began attacks on Serbian police and politicians and were engaged in an all-out uprising by 1998.Serbian and Yugoslav forces tried to fight growing KLA support through oppressive tactics and violence. The government destroyed villages and forced people to leave their homes. They massacred entire villages. Many people fled their homes.As the conflict grew worse, international intervention rose. The Contact Group (consisting of the U.S., Britain, Germany, France, Italy and Russia) demanded a cease-fire, the withdrawal of Yugoslav and Serbian forces from Kosovo and the return of refugees. Yugoslavia at first agreed but ultimately failed to implement the terms of the agreement.Yugoslav and Serbian forces engaged in an ethnic cleansing campaign throughout the duration of the war. By the end of May 1999, 1.5 million people had fled their homes. At the time, that constituted approximately 90 percent of Kosovo’s population.Diplomatic negotiations between Kosovar and Serbian delegations began in France in 1999, but Serbian officials refused to cooperate. In response, NATO began a campaign of airstrikes against Serbian targets, focusing mainly on destroying Serbian government buildings and infrastructure. The bombings caused further flows of refugees into neighboring countries and the deaths of several civilians.In June 1999, NATO and Yugoslavia signed a peace accord to end the Kosovo War. The Yugoslav government agreed to troop withdrawal and the return of almost one million ethnic Albanians and half a million general displaced persons. Unfortunately, tensions between Albanians and Serbs continued into the 21st century. Anti-Serb riots broke out in March 2004 throughout the Kosovo region. Twenty people were killed and over 4,000 Serbs and other minorities were displaced.In February 2008, Kosovo declared independence from Serbia. Subsequently, Yugoslavia ceased to exist in 2003 and became the individual countries of Serbia and Montenegro. Serbia, along with numerous other countries, refused to recognize Kosovo’s independence.At the end of 2016, a tribunal was established in the International Criminal Court to try Kosovars for committing war crimes against ethnic minorities and political opponents. Additionally, an EU taskforce set up in 2011 found evidence that members of the KLA committed these crimes after the war ended. Previously, the U.N. International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia tried several the KLA members.

UN's International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the Hague, talked of indiscriminate killings and as many as 100,000 civilians missing or taken out of refugee columns by the Serbs.7,000 Bosnian Muslims died in the week-long Srebrenica massacre in 1995, less than 3,000 Kosovo Albanian murder victims have been discovered in the whole of Kosovo. "The final number of bodies uncovered will be less than 10,000 and probably more accurately determined as between two and three thousand.

UN's International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the Hague, talked of indiscriminate killings and as many as 100,000 civilians missing or taken out of refugee columns by the Serbs.7,000 Bosnian Muslims died in the week-long Srebrenica massacre in 1995, less than 3,000 Kosovo Albanian murder victims have been discovered in the whole of Kosovo. "The final number of bodies uncovered will be less than 10,000 and probably more accurately determined as between two and three thousand.

Genocide

The skull of a victim of the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre in an exhumed mass grave outside of Poto?ari, 2007.It is widely considered that mass murders against Bosniaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina escalated into genocide. On 18 December 1992, the United Nations General Assembly issued resolution 47/121 condemning "aggressive acts by the Serbian and Montenegrin forces to acquire more territories by force" and called such ethnic cleansing "a form of genocide". In its report published on the 1 January 1993, Helsinki Watch was one of the first civil rights organisations that warned that "the extent of the violence and its selective nature along ethnic and religious lines suggest crimes of genocidal character against Muslim and, to a lesser extent, Croatian populations in Bosnia-Hercegovina".A trial took place before the International Court of Justice, following a 1993 suit by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia and Montenegro alleging genocide. The ICJ ruling of 26 February 2007 indirectly determined the war's nature to be international, though clearing Serbia of direct responsibility for the genocide committed by the forces of Republika Srpska. The ICJ concluded, however, that Serbia failed to prevent genocide committed by Serb forces and failed to punish those responsible, and bring them to justice. A telegram sent to the White House on 8 February 1994 and penned by U.S. Ambassador to Croatia, Peter W. Galbraith, stated that genocide was occurring. The telegram cited "constant and indiscriminate shelling and gunfire" of Sarajevo by Karadzic's Yugoslav People Army; the harassment of minority groups in Northern Bosnia "in an attempt to force them to leave"; and the use of detainees "to do dangerous work on the front lines" as evidence that genocide was being committed. In 2005, the United States Congress passed a resolution declaring that "the Serbian policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing meet the terms defining genocide".Despite the evidence of many kinds of war crimes conducted simultaneously by different Serb forces in different parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially in Bijeljina, Sarajevo, Prijedor, Zvornik, Banja Luka, Vi?egrad and Fo?a, the judges ruled that the criteria for genocide with the specific intent (dolus specialis) to destroy Bosnian Muslims were met only in Srebrenica or Eastern Bosnia in 1995. The court concluded that other crimes, outside Srebrenica, committed during the 1992-1995 war, may amount to crimes against humanity according to the international law, but that these acts did not, in themselves, constitute genocide per se.The crime of genocide in the Srebrenica enclave was confirmed in several guilty verdicts handed down by the ICTY, most notably in the conviction of the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic.Ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon in the wars in Croatia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This entailed intimidation, forced expulsion, or killing of the unwanted ethnic group as well as the destruction of the places of worship, cemeteries and cultural and historical buildings of that ethnic group in order to alter the population composition of an area in the favour of another ethnic group which would become the majority. These examples of territorial nationalism and territorial aspirations are part of the goal of an ethnically pure nation-state.According to numerous ICTY verdicts and indictments, Serb and Croat forces performed ethnic cleansing of their territories planned by their political leadership to create ethnically pure states (Republika Srpska and Republic of Serbian Krajina by the Serbs; and Herzeg-Bosnia by the Croats).According to the ICTY, Serb forces deported at least 80-100,000 Croats in Croatia in 1991-92 and at least 700,000 Albanians in Kosovo in 1999. Further hundreds of thousands of Muslims were forced out of their homes by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina. By one estimate, the Serb forces drove at least 700,000 Bosnian Muslims from the area of Bosnia under their control.War rape in the Yugoslav Wars has often been characterized as a crime against humanity. Rape perpetrated by Serb forces served to destroy cultural and social ties of the victims and their communities. Serbian policies allegedly urged soldiers to rape Bosniak women until they became pregnant as an attempt towards ethnic cleansing. Serbian soldiers hoped to force Bosniak women to carry Serbian children through repeated rape. Often Bosniak women were held in captivity for an extended period of time and only released slightly before the birth of a child conceived of rape. The systematic rape of Bosniak women may have carried further-reaching repercussions than the initial displacement of rape victims. Stress, caused by the trauma of rape, coupled with the lack of access to reproductive health care often experienced by displaced peoples, lead to serious health risks for victimized women.During the Kosovo War thousands of Kosovo Albanian women and girls became victims of sexual violence. War rape was used as a weapon of war and an instrument of systematic ethnic cleansing; rape was used to terrorize the civilian population, extort money from families, and force people to flee their homes. According to a report by the Human Rights Watch group in 2000, rape in the Kosovo War can generally be subdivided into three categories: rapes in women's homes, rapes during flight, and rapes in detention. The majority of the perpetrators were Serbian paramilitaries, but also included Serbian special police or Yugoslav army soldiers. Virtually all of the sexual assaults Human Rights Watch documented were gang rapes involving at least two perpetrators. Since the end of the war, rapes of Serbian, Albanian, and Roma women by ethnic Albanians sometimes by members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) - have been documented. Rapes occurred frequently in the presence, and with the acquiescence, of military officers. Soldiers, police, and paramilitaries often raped their victims in the full view of numerous witnesses.Later, the remaining Yugoslav republics of Macedonia and Montenegro seceded, as did the former autonomous province of Kosovo. In each case, violence against civilians defined along identity-based lines existed, most intensely so in Kosovo. In 1999, a multilateral force conducted a ten-week-long bombing campaign against Serbian forces, whom Western leaders feared were set to wage another campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo as a response to Kosovo’s independence aspirations.A UN war crimes tribunal has convicted Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic of genocide and sentenced him to life imprisonment.He was convicted of the massacre of more than 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys at Srebrenica in 1995, and the siege of Sarajevo in which more than 10,000 people died.The 74-year-old was removed from the courtroom just before his sentence was read for shouting at the judges and causing a disturbance.The court also found that "genocide, persecution, extermination, murder and the inhuman act of forcible transfer were committed in or around Srebrenica" in 1995, said presiding judge Alphons Orie.

The former Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladić, nicknamed the ‘butcher of Bosnia’, has been sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.More than 20 years after the Srebrenica massacre, Mladic was found guilty at the United Nations-backed international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague of 10 offences involving extermination, murder and persecution of civilian populations.

The former Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladić, nicknamed the ‘butcher of Bosnia’, has been sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity.More than 20 years after the Srebrenica massacre, Mladic was found guilty at the United Nations-backed international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague of 10 offences involving extermination, murder and persecution of civilian populations.