SYRIAN CIVIL WAR,BASHAR AL ASSAD REGIME,MUCH LIKE HIS FATHER'S HAFEZ AL - ASSAD,IS A REGIME OF MINORITIES.HIS LEGACY ASSISTED BASHAR IN HOLDING ON TO POWER EVEN AS HIS CONTEMPORARY AUTHORITARIAN RULES SUCCUMBED TO THE WHIRLPOOL THAT WAS THE ARAB SPRING.

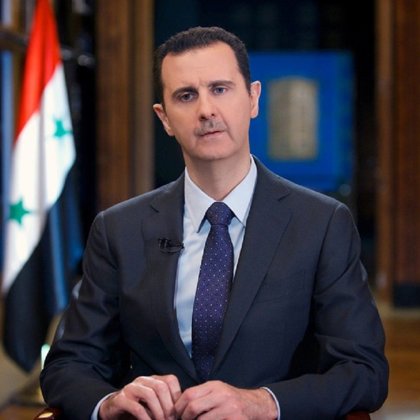

Bashar al-Assad (born 1965), is the President of Syria since 2000. Before Bassel's death he was an ophthalmologist. He is married to Asma al-Assad (born 1975). She is the First Lady of Syria and takes a prominent public role. Before being married she was an investment banker. They have three children.

Bashar al-Assad (born 1965), is the President of Syria since 2000. Before Bassel's death he was an ophthalmologist. He is married to Asma al-Assad (born 1975). She is the First Lady of Syria and takes a prominent public role. Before being married she was an investment banker. They have three children.

Syria’s fate changed drastically on June 10, 2000, the day Hafez al-Assad (1971–2000) succumbed to a heart attack in Damascus. The Lion of Damascus was no more. Left behind was a carefully constructed authoritarian structure that had sustained three decades of unrivaled power in Syria. Hafez al Assad’s most enduring legacies knit together the Alawite community and other minorities. He acquiesced to the Sunni elite, created an effective secret services, and most of all appointed the next ruler of Syria, the quiet, multilingual, tech savvy ophthalmologist, Bashar al-Assad. The Assad legacy assisted Bashar in holding on to power even as his contemporary authoritarian rulers succumbed to the whirlpool that was/is the Arab Spring.Syria is at the heart of a conflict that has irreversibly changed the politics of the Middle East. While most other authoritarian regimes dwindled and eventually collapsed, the Assad regime has proven to be, to the surprise of many, relatively steadfast. The survival of the Assad regime despite a full throttle pro- democracy movement and a brutal, lengthy civil war can be explained by the institutional and strategic strengths the regime enjoys. Loyalty of the Army, a mandate from minorities and moderates who fear an Islamist takeover, constant support from the Sunni elite, and military backing from Iran and Russia have enabled the Assad regime to stand firm against all odds. The unrelenting claim to the throne is reflective of the legacy of authoritarianism in Syria.Assad’s regime, much like his father’s, is a regime of minorities. Governing a Sunni population of over 74%, the Assad family belongs to a Shiite ethno-religious sect called the Alawites. The Alawites bear a peculiar, troubling history as a minority. Not only is there religious tension between the Shiite and Sunni sects of Islam, the Alawites are viewed pejoratively also by the fellow Shiite groups for having ‘heretical’ tendencies. They are a minority within a minority.In an identity conscious society like Syria’s, the ethno-religious divisions are barely forgotten and rarely do they lose significance. Apart from the Sunni – Shiite division, Syria also hosts a considerable population of other minorities which include, among others, Christians, Jews, Kurds, and Druze. Syrians of different religious traditions speak the same language, share ancestral legacy and yet the identity politics of ethnicity and religion almost always plays a significant part in Syrian polity. A central element of the Syrian authoritarian structure is the support it receives from a coalition of all minorities. In a typical act of self- preservation the minorities have historically lent support to the regime for any alternatives that would place them at a great disadvantage, physically and economically. Assad’s regime, from the time of Hafez al-Assad till this day, enjoys unwavering support from the minorities for it is viewed as a protector of minority interests in Syria, and the regime itself belongs to a minority.The carefully engineered minority domination in the bureaucracy and the army has ensured that defections remain at a bare minimum. Unlike the fragile regimes of Muammar Gaddafi, Hosseini Mubarak and Ben Ali, the state apparatus and the army have stood by the Syrian regime, mostly for self- preservation purposes. The network of minority domination that exists in Syria is pure genius in that the minorities not only lend protection to the Assad family but to each other as well. It is a typical example of mutual protection. In Libya, for example, the weakened state institutions were exclusive of each other working mostly as separate entities protecting the interests of the ruler, Gaddafi, and of those close to him. Such a system of weak interdependence was bound to fail simply because the state apparatus had no existential stake in protecting the regime once trouble hit the shores of Libya. In Syria the case is exactly to the contrary.

The most

Syrians support the government. It was not the case in 2011–2012 where

the unrest was really strong and the government had very little

credibility.But the events of the Syrian Civil War have persuaded many that rebellion was really bad.The

rebels enjoyed the support of neighboring countries such as Turkey and

Jordan whose goal at least for Turkey was to annex part or totality of

the country.

The most

Syrians support the government. It was not the case in 2011–2012 where

the unrest was really strong and the government had very little

credibility.But the events of the Syrian Civil War have persuaded many that rebellion was really bad.The

rebels enjoyed the support of neighboring countries such as Turkey and

Jordan whose goal at least for Turkey was to annex part or totality of

the country.

The

original protesters had nothing or very little to do with the extremism

that very quickly usurped them. Their gripe was more than justified and

Assad reacted with the similarly mindless brutality that his father had

used years ago.Yet his slaughter opened the door to escalation very quickly, providing a playground for the extremist elements that entered.So

what started as an oppressed people rightfully demanding greater

freedom turned into fanatic partisanship of pseudoreligious agenda.

Ironically with neither the extremists (totally unrepresentative of

Sunny Islam) nor the principally secular Assad crowd representing any

religion at all, least not truthfully.

The

original protesters had nothing or very little to do with the extremism

that very quickly usurped them. Their gripe was more than justified and

Assad reacted with the similarly mindless brutality that his father had

used years ago.Yet his slaughter opened the door to escalation very quickly, providing a playground for the extremist elements that entered.So

what started as an oppressed people rightfully demanding greater

freedom turned into fanatic partisanship of pseudoreligious agenda.

Ironically with neither the extremists (totally unrepresentative of

Sunny Islam) nor the principally secular Assad crowd representing any

religion at all, least not truthfully.

The conflict in Syria transitioned from an insurgency to a civil war during the summer of 2012. For the first year of the conflict, Bashar al-Assad relied on his father’s counterinsurgency approach; however, Bashar al-Assad’s campaign failed to put down the 2011 revolution and accelerated the descent into civil war. This report seeks to explain how the Assad regime lost its counterinsurgency campaign, but remains well situated to fight a protracted civil war against Syria’s opposition.Hafez al-Assad subdued the Muslim Brotherhood uprising in the early 1980s through a counterinsurgency campaign that relied on three strategies for generating and employing military force: carefully selecting and deploying the most trusted military units, raising pro-regime militias, and using those forces to clear insurgents out of major urban areas and then hold them with a heavy garrison of troops. Bashar al-Assad attempted unsuccessfully to employ the same strategy in 2011-2012.Bashar al-Assad’s reliance on a small core of trusted military units limited his ability to control all of Syria. He hedged against defections by deploying only the most loyal one-third of the Syrian Army, but in so doing he undercut his ability to prosecute a troop-intensive counterinsurgency campaign because he could not use all of his forces. Defections and attrition have exacerbated the regime’s central challenge of generating combat power. These dynamics have weakened the Syrian Army in some ways but also honed it, such that what remains of these armed forces is comprised entirely of committed regime supporters.Pro-Assad militias have become the most significant source of armed reinforcement for the Syrian Army. The mostly-Alawite shabiha mafias are led by extended members of the Assad family and have been responsible for some of the worst brutality against the Syrian opposition. The local Popular Committees draw their ranks from minorities who have armed themselves to protect their communities against opposition fighters. Both types of militia coordinate closely with and receive direct support from the regime, as well as from Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) and Lebanese Hezbollah.Bashar al-Assad’s forces have displaced populations in opposition strongholds, which has deepened Syria’s sectarian division. The regime has employed artillery, air power, bulldozers, sectarian massacres, and even ballistic missiles to force Syrian populations out of insurgent held areas. This strategy ensures that even when the rebels win towns and neighborhoods, they lose the population. Chemical weapons are now the only unused element in Assad’s arsenal, which could be used for large-scale population displacement to great effect.Fears of retribution have pushed conventional and paramilitary loyalists to converge upon the common goal of survival, resulting in a broadly cohesive, ultra-nationalist, and mostly-Alawite force. The remnants of the Syrian military and the powerful pro-regime militias are likely to wage a fierce insurgency against any opposition-led Sunni government in Syria if the Assad regime collapses. Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah are likely to encourage the militias and regime remnants to converge, supporting this transition to insurgency in order to preserve Iranian interests after Assad.The regime has concentrated conventional forces in Damascus and Homs. The relatively small force deployed to northern and eastern Syria have disrupted rebel advances, but isolated strongpoints have been overrun as the regime struggles to maintain logistical lines of communication. The majority of the regime’s deployable forces have remained in Homs and Damascus, where rebels have made significant gains but remain unable to dislodge regime troops.Assad is unlikely to regain control over all of Syria, although he is well situated to continue fighting in 2013 and to prevent the opposition from taking over the rest of the country. The regime has contracted around a corridor that connects Damascus, Homs, and the coast, and Assad can continue to rely on a broadly cohesive and mostly Alawite core of soldiers and militias, backed by Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah.Russia has been ardently opposed to all of the bellicose meddling in the internal affairs of sovereign nations. President Putin has stated on numerous occasions that there needs to be a new global platform of international relationships built on the foundation of implicit respect for national sovereignty. He has expressed that the world community of nations is obligated to reject the outside interference of those powerful nations which routinely commit actions of naked aggression.Assad is more likely to continue fighting in Damascus and Homs than to retreat to the coast in 2013, although it will become difficult for the regime to claim to govern Syria if the opposition breaks into downtown Damascus. Assad is more likely to destroy Damascus than to abandon it to the opposition. Hopes of a clean opposition victory and a peaceful transition are therefore dim.In the buildup prior to the premeditated terminations of Saddam and Gadhafi regimes Western media took turns at demonizing these leaders, who have done much to their people than any leaders in the West, by showing images of violence supposedly committed by these dictators against some sectors in their own societies which were proven to be CIA/Mossad inflicted.They could not do the same with President Assad of Syria, because internally he has no enemies.

Russia has come under increasing criticism from Western nations for its

attacks on rebel-held east Aleppo, with the US and several prominent

political figures accusing Moscow of war crimes.The deliberate targeting of hospitals, medical personnel, schools and

essential infrastructure, as well as the use of barrel bombs, cluster

bombs, and chemical weapons, constitute a catastrophic escalation of the

conflict and may amount to war crimes.

Russia has come under increasing criticism from Western nations for its

attacks on rebel-held east Aleppo, with the US and several prominent

political figures accusing Moscow of war crimes.The deliberate targeting of hospitals, medical personnel, schools and

essential infrastructure, as well as the use of barrel bombs, cluster

bombs, and chemical weapons, constitute a catastrophic escalation of the

conflict and may amount to war crimes.

The Russian military intervention, launched in September 2015, has always remained limited in scale, but Putin’s personal diplomacy worked as a force multiplier. He has been able to communicate with just about every stakeholder in the Syrian calamity, from Iran to Saudi Arabia, and from Israel to Hezbollah. The only message he is now trying to convey to his interlocutors is a vague promise not to interfere with their strikes and counter-strikes, which leaves few of them satisfied. The limits of Russian power projection capabilities have become exposed, and political ambivalence has aggravated that weakness. Putin keeps talking with Middle Eastern peersfor instance with Mahmoud Abbas, presented on the Kremlin website as “President of the State of Palestine”but avoids elaborating on these matters, perhaps assuming that the Syrian theme doesn’t work all that well for his re-election campaign.Establishing functional political and military cooperation with Iran and Turkey was a major breakthrough for Russia’s Syrian policy in 2017. The “brotherhood in arms” with Iran had been forged in fall 2015, as Russian bombers provided close air support for Iran-trained Shiite militias. Turkey, at that time, was fiercely opposed to the Russian intervention (after a Turkish F-16 shot down a Russian Sukhoi Su-24M in November 2015, for instance, it took months for the bitter quarrel to be resolved). Putin has exploited Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s fears, driven by the coup attempt in July 2016, and pulled him into the triangular proto-alliance with Iran aimed at enforcing a ceasefire in Syria on terms beneficial for Assad. The November 2017 trilateral Putin-Erdoğan-Rouhani summit in Sochi was the culmination of that effort, but with the military defeat of ISIS, the three “peace enforcers” went their different ways.For Turkey, as another one of my Brookings colleagues Kemal Kirişci argues, the fight against ISIS was always of secondary importance, while the main battle was with the Syrian Kurds. Erdoğan is distraught about U.S. support for the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which has been the main fighting force in capturing Raqqa and pushing ISIS into far corners of Syrian desert. Seeking to break this alliance, Turkey launched an offensive into the Kurdish enclave Afrin in January. Russia had cultivated ties with the Kurds, but opted for sacrificing this “friendship” and gave consent for the Turkish attack when Chief of General Staff General Hulusi Akar and Chief of National Intelligence Hakan Fidan visited Moscow shortly before the offensive began. The Russian leadership has good reasons to assume that U.S.-Turkish tensions will escalate because of the Afrin offensive, so Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov accuses Washington of ignoring Turkish concerns and building a “quasi-state” for Kurds in northeastern Syria. Meanwhile, the Turkish forces are encountering stiff resistance in Afrin, and Moscow is quietly encouraging the Assad regime to provide support for the Kurds.For Iran, the key goal in Syria is to consolidate its military positions so that it can put pressure on the vulnerabilities of deployed U.S. forces and directly threaten Israel. Russian high command had deep reservations about Tehran’s plan to build a structure in Syria resembling the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, instead of propping up the unreliable army. Israel’s severe retaliation for the recent Iranian drone incursion has pushed Russian policy into an awkward limbo. Putin highly values his personal ties with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and Russian air defense assets deployed in its Tartus and Khmeimim bases and covering most of Syrian airspace did not interfere with Israel’s air strikes. The “made-in-Russia” Syrian air defense managed, nevertheless, to down one Israeli fighter plane, and now after losing about a half of its assets this system needs to be rebuilt, and Damascus will demand help from Moscow.

Turkey is wary of the presence of Kurdish fighters close to its borders

in both Syria and Iraq. It associates the fighters with anti-Ankara

Kurdish militants and has deployed troops to both of Arab countries

without their approval to rein in their movements. Bashar al-Assad is backed in the war by Russia, Iran

and militias including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and its campaign against IS

has mostly been on the west bank of the river.

Turkey is wary of the presence of Kurdish fighters close to its borders

in both Syria and Iraq. It associates the fighters with anti-Ankara

Kurdish militants and has deployed troops to both of Arab countries

without their approval to rein in their movements. Bashar al-Assad is backed in the war by Russia, Iran

and militias including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and its campaign against IS

has mostly been on the west bank of the river.